Saying Goodbye to My Ancestral Home

Photo: Wan Phing Lim

225 Jalan Pemancar, Gelugor, Penang | 1,500 words

When Great-Grandma died, my sister crawled underneath her casket playing hide and seek. First Aunt—my eldest grandaunt—shooed her away, then came into the piano room to tell us not to press on the keys, tong tong tong, for guests were still out in the living area paying their respects.

Before First Aunt died, she told me not to shake my legs at the dinner table, for that is not what a young lady does. At tea time, Second Aunt would bring out the jam tarts and kopi-o, a clay mug for everyone on Pimpernel placemats. Third Aunt would shrink in her chair, quiet as she always was, doting on the husband who was seeing another woman.

Fourth Aunt would rarely come back from Singapore, Fifth Aunt was further away still in Mombasa. Sixth Aunt lived just down the road so she came by all the time, Eighth Aunt was still in Essex, while Seventh Aunt was long gone, from lung cancer in London. Whose turn will it be next?

My ancestral home in Gelugor was not always there. Every migrant, economic or refugee, knows how long the road to comfort and prosperity can be. For Great-Grandma and Grandpa, it was riddled with sibling rivalry, a great depression, a second world war, independence from Britain and a post-Malaya identity crisis.

The double-storey house on Jalan Pemancar in Gelugor stands tall and aloof, with a twin brother next door made in a mirror image. One was sold for profit and the other kept for posterity. Commissioned by my grandfather for his parents, it was constructed in the 1960’s architectural style, clean and spare, rectangular and functional in symmetrical lines. Only glass, stone and wood embellish it. The floors are tiled with two-by-two-centimetre stone mosaics, laid by hand piece by piece, never cutting anyone’s toes, only cooling your feet on a hot day in suburban Gelugor.

Eight sisters and their two brothers lived there with their parents, Lim Lan Kok and Chuah Pheck Eng, patriarch and matriarch, migrants born in Fujian Province, China in 1899 and 1904 respectively. Theirs was the generation brave enough to uproot and leave, and with their first-borns in tow, a boy and a girl, they travelled by sea to Singapore in 1929 and then to Penang in 1938. The family moved in in the year 1975, but now the patriarch and matriarch have long gone, and the ten at home have whittled down to one.

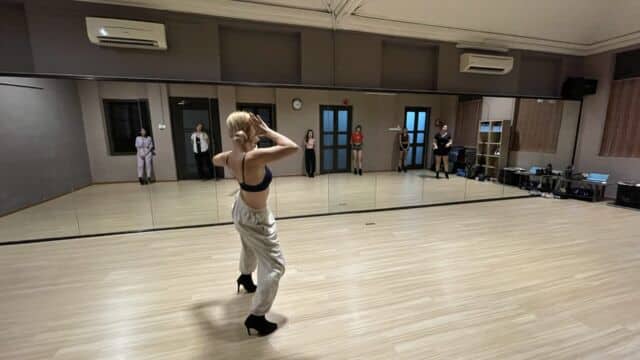

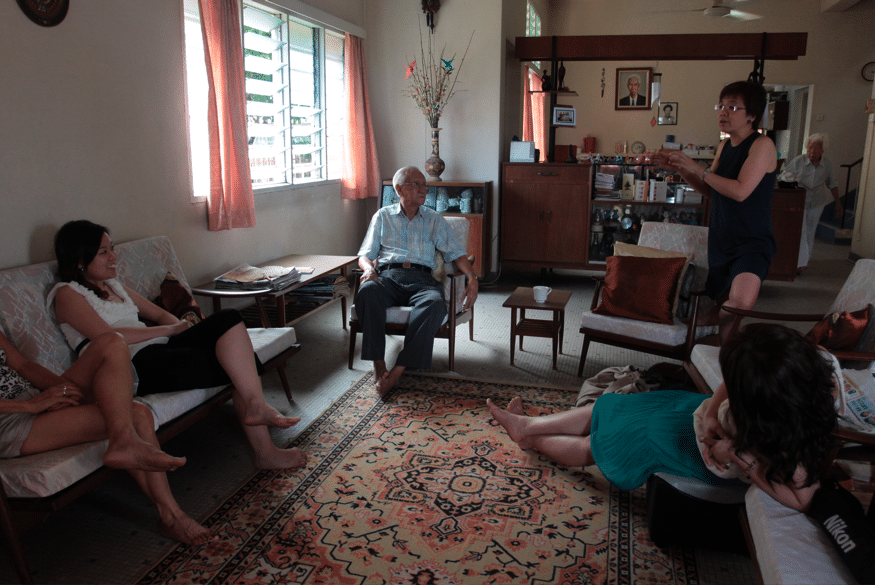

Grand Uncle at the age of 95 sits alone on his armchair with the ceiling fan turned off. Second Aunt and Third Aunt have gone too: it’s strange how the girls have gone first. There are now two boys and four girls.

What is a house without its inhabitants, a home without a family? When the people go, the place goes too.

*

When the For Sale sign goes up, I take a photo of it and send it to my father’s sister in London.

“As expected,” she replies. “Ask how much she is selling?” – referring to Grand Uncle’s daughter, owner of the house by deed.

“About three point five million,” I say.

“She’s not going to get that,” comes the reply. “This isn’t Minden Heights, it’s only Gelugor.”

Only Gelugor, I think, only Gelugor. Gelugor of asam gelugur, tropical wild fruit, sliced, dried and thrown into curries and soups.

You see, I tell the house, you are only Gelugor, not Minden Heights next door, named for Germany’s Battle of Minden. Not David Brown’s “Glugor House and Spice Plantation” either, from an 1818 oil painting that hangs in the Penang Museum. Even the Brown home was later renamed Minden Barracks—there you go.

The For Sale sign raises an alarm within me, and I ask Grand Uncle’s daughter not to throw anything away, especially old photographs. I say there may be something there of my father or grandfather’s. I go over to open cupboards, pull drawers, leaf through wads of yellowing paper. There’s an urgency inside of me, but for what?

Grand Uncle is alone at home with his live-in help, Sahram, a lady from Lombok in Indonesia. She makes me a cup of Sailor brand kopi-o, Grand Uncle’s favourite Hailam coffee brand. Except it is 2-in-1 with sugar in it, and I don’t take sugar in my coffee. But it’s ok, I say. On my next trip I’ll bring my own sachet of kopi-o, 1-in-1.

In a cupboard in the piano room, I find a calligraphy scroll from China, postcards from the Palace Museum of Peking, a handwritten recipe for homemade Vicks (450gm vaseline, 350gm wax, 37g camphor powder, 37g menthol crystal, 37g thymol powder, 600gm methyl salicylate, 450ml eucalyptus oil).

Lined up on the bookshelf are Children’s Britannica volumes one to twenty, the Encyclopaedia Britannica one to thirty, the Encyclopedia Americana one to thirty. I’m in a museum, with objects from the dead and the living living together. Who wants any of this stuff? Nobody and everybody.

I find remnants of lives lived and gone: a Federation of Malaya Malayan Driving Licence, a Malayan Banking Berhad Savings Account Passbook, a Hire Purchase Agreement for the Singer Sewing Machine Company as thick as a brochure, signed in 1972 in long, slanty curves.

There’s a HOC 900x microscope, Philips’ Malaysia and Singapore Modern School Atlas, ping pong bats and balls, plastic whistles for a PE teacher—remains from a school supply store the family used to run on Carnarvon Street in the 1970s.

In a shoebox of photographs in many envelopes, I find travel postcards from New Zealand (“To Kathleen, from your penpal Rod”). Which grandaunt is Kathleen? I know them only by number—it turns out to be Fifth Aunt, the one who lives in Kenya, the one whose real name is Koon Choo. The girls are all Koon-something, and the boys are all Chuin-something.

What old-fashioned dialect names they have: Bean, Lay, Tee, Hooi, Choo, Ho, Beng and Tiat. Names that sound neither male nor female, names that are no longer popular today. So who could blame them if they became Jackie, Kathleen, Rebecca, Isobel and Christine? Can we blame anyone for staying or going, for living or dying?

Mum and Dad spoke not a word of English, but sent us to ballet classes at the YWCA, to cooking classes at Lor Meiling’s on Lengkok Lumba Kuda. They sent us off to England to be nurses, and so we married Englishmen, German men, Indian men, Singaporean men, and never came home… So they tell me.

*

When its inhabitants are all gone, a house becomes a ghost. Or it becomes a shell. A ghost in a shell. Is Grand Uncle ghost or shell? He is stooped to the ground, his name is Chong. His bed is now in the piano room, surrounded by shoeboxes of asthma inhalers and medications on table tops.

The television is no longer turned on, for nobody watches television anymore, not even the 95-year-old. Grand Uncle is hiding behind his phone—the same way his father used to hide behind orchids—sending a WhatsApp message to his children in Singapore, playing a game of crosswords and sudoku, or looking at today’s empat ekor lottery numbers.

The pemancar in Jalan Pemancar – pemancar being a Malay word for a transmitter or siren – is gradually weakening, just like its occupants, old folks in bungalow homes dotted along the street’s twisty J-curve. They are hemmed in now by 46-storey high-rises with names like Ideal Venice Residency, that boast of housing over one thousand families.

Still, the rambutan tree in the backyard waits for a family, for children and grandchildren. They’ll come not by sea now, but by mechanical birds. The rambutan tree waits, dropping its fruits to the ground for the ants instead.

A disused Bellings oven in the outdoor kitchen is waiting to make First Aunt’s famous pat poh ak (eight jewel duck), if it can be turned on again. In the indoor kitchen, there’s a rusty weighing scale one sees only in wet markets, a little coffee table for one in a corner, and a kettle that burns on the gas stove. In this home, my parents were married in 1978, and many a Chinese New Year reunion dinner was held here.

Out front in the living area, Great-Grandma’s stuffed bear—a Quasimodo-like creature nicknamed “Heh Koo”, the Hokkien word for asthma, for it looks like an asthmatic bear—has outlasted her on her wooden rocking chair.

An open shelving partition separates the dining area from the living room, making the house larger than it seems. Its sideboards, cabinets, armchairs and coffee tables are well- proportioned; wooden, slim, with smooth flat surfaces. This house in Gelugor was good design even before I knew good design. It is modern even when it is not.

When the For Sale sign is taken down, the “land bankers”, as they’re known, won’t care about any of this. They’ll raze the house to the ground, throw out everything inside. A different child will play on a different piano, a different child will crawl underneath someone else’s casket.

After all, nostalgia is for the weak, and progress is about looking forward, always to the future.

© Wan Phing Lim

Commissioning editor: Anna Tan